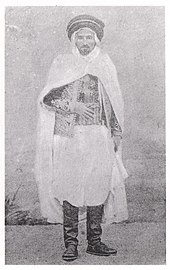

Bou Mezrag El Mokrani, circa 1874.

Louise: “Bread, work, or lead”.

FUTURE: “One without exploiters and without exploited.”

Kanak people and Culture, Bichelamar Creole.

Louise Michel in New Caledonia

A biography of Louise Michel during her exile in New Caledonia, and after her 1880 return to Paris following amnesty.

GARE SAINT LAZARE

Louise Michel in New Caledonia

After twenty months in prison Louise was loaded onto the ship the Virginie on 8 August 1873 to be deported to New Caledonia, where she arrived four months later. Whilst on board, she became acquainted with Henri Rochefort, a famous polemicist, who became her lifelong friend. She also met Nathalie Lemel, another figure active in the Commune. It was this latter contact that led Louise to become an anarchist. She remained in New Caledonia for seven years and befriended the local Kanak people.

Taking an interest in Kanak legends, cosmology and languages, particularly the bichelamar creole, she learned about Kanak culture from friendships she had made with Kanak people. She taught French to the Kanaks and took their side in the 1878 Kanak revolt. The following year, she received authorisation to become a teacher in Nouméa for the children of the deported — among them many Algerian Kabyles (“Kabyles du Pacifique”) from Cheikh Mokrani’s 1871 rebellion.

The 1880 amnesty and her return to France

In 1880, amnesty was granted to those who had participated in the Paris Commune. Louise returned to Paris, her revolutionary passion undiminished. She gave a public address on 21 November 1880 and continued her revolutionary activity in Europe, attending the anarchist congress in London in 1881, where she led demonstrations and spoke to huge crowds. While in London, she also attended meetings at the Russell Square home of the Pankhursts where she made a particular impression on a young Sylvia Pankhurst. In France she successfully campaigned, together with Charles Malato and Victor Henri Rochefort, for an amnesty to be also granted to Algerian deportees in New Caledonia.

In March 1883 Louise and Émile Pouget led a demonstration of unemployed workers. In a subsequent riot, 500 demonstrators pillaged three bakeries and shouted “Bread, work, or lead”. Louise was accused of having led this demonstration with a black flag, which has since become a symbol of anarchism.

Louise was tried for her actions in the riot and used the court to publicly defend her anarchist principles. She was sentenced to six years of solitary confinement for inciting the looting. She was defiant at her trial; for her, the future of the human race was at stake, “One without exploiters and without exploited.” She was released in 1886, at the same time as Kropotkin and other prominent anarchists.

In 1888, Louise survived an assassination attempt when Pierre Lucas shot her head point-blank. A bullet lodged in the left side of her skull and could never be removed. Louise refused to press charges against him, wrote numerous letters requesting that the police charges be dropped, and paid a lawyer to represent him at trial. You can read a newspaper article about the event here.

United Nations Human Rights Amnesty International Bichelamar Creole

- Bichelamar

SOURCE

Amnesty International, UK

Deklereisen Blong Raet Blong Evri Man Mo Woman Raon Wol

FESTOK

From se Jenerol Asembli i luksave respek mo ikwol raet blong man mo woman olsem stamba blong fridom, jastis mo pis long wol,

From se fasin blong no luksave mo no respektem ol raet blong man mo woman i mekem se i gat ol nogud aksen i tekemples we oli mekem se pipol i kros, mo bambae wan taem i kam we pipol bambae i glad long fridom blong toktok mo biliv blong hem, fridom blong no fraet mo wantem samting hemi kamaot olsem nambawan tingting blong ol grasrut pipol,

From se hemi wan impoten samting, sipos man i no fos blong lukaotem help, olsem wan las aksen we hemi save mekem, blong faet agensem rabis fasin blong spoelem no fosem pipol hemia blong mekem nomo se Loa i protektem ol raet blong man mo woman,

From se i gat nid blong promotem fasin blong developem frensip wetem ol narafala kaontri,

From se ol pipol blong Unaeted Neisen oli talem bakegen insaed long Jata strong tingting blong olgeta long ol stamba raet blong man mo woman, respek mo valiu blong man mo woman mo long ikwol raet blong man mo woman, oli disaed blong promotem sosol progres mo ol standed blong laef we i moa gud mo we i gat moa fridom,

From se ol Memba Kaontri oli mekem strong promis blong promotem respek blong ol raet blong man mo woman olbaot long wol mo gat ol stamba fridom taem we oli stap wok tugeta wetem Unaeted Neisen,

From se hemi impoten tumas blong evriwan i luksave ol raet mo fridom blong promis ia i save tekemples fulwan,

Hemi mekem se JENEROL ASEMBLI i putumaot

Deklereisen blong ol Raet blong evri Man mo Woman Raon long Wol olsem wan impoten samting we evri pipol mo evri kaontri long wol oli mas kasem, blong mekem se wanwan man mo woman insaed long sosaeti oli tingting oltaem long Deklereisen ia, bambae oli wok had tru long tijing mo edukeisen blong leftemap resek long ol raet mo fridom ia mo tru ol step we oli tekem long nasonol mo intenasonol level, blong mekem se ol pipol blong ol Memba Kaontri mo ol pipol blong ol teritori we oli stap anda long olgeta blong oli luksave mo folem Deklereisen ia.

Atikol 1

Evri man mo woman i bon fri mo ikwol long respek mo ol raet. Oli gat risen mo tingting mo oli mas tritim wanwan long olgeta olsem ol brata mo sista.

Atikol 2

Evriwan i gat raet long evri raet mo fridom we i stap long Deklereisen ia, wetaot eni kaen difrens, olsem long reis, kala blong skin, seks, langwis, rilijen, politikol o narafala kaen tingting, we i kamaot long saed blong neisen o sosol, propeti, taem we man i bon long hem o emi narafala sosol saed olsem.

Andap long hemia, bambae wan man o woman i no save mekem eni difrens long level blong politik, eria we wok hem i kavremap o intenasonol level blong kaontri o teritori blong narafala man o woman ia, nomata we hemi indipenden, tras, non-self-gavening o anda eni narafala arenjmen blong soverenti.

Atikol 3

Evriwan i gat raet blong laef, fridommo sekuriti blong man mo woman.

Atikol 4

Bambae man i no tekem narafala man o woman olsem slev blong hem. Bambae hemi agensem loa blong eni kaen fasin blong slev mo fasin blong salem man o woman olsem slev i tekemples.

Atikol 5

Bambae man mo woman i no save mekem fasin blong mekem narafala man o woman i safa o mekem rabis fasin long hem, fasin we i nogud long man o woman o tritim man o woman long fasin o panismen we i soem se man o woman i luk daon long man o woman.

Atikol 6

Evriwan i gat raet blong narafala man i luksave hem olsem wan man o woman we i stap anda long loa.

Atikol 7

Evri man mo woman i semak folem loa mo oli gat semak raet wetaot eni diskrismineisen blong loa i protektem olgeta. Evri man mo woman oli gat raet blong loa ia i protektem olgeta long ikwol fasin agensem diskrimineisen long taem we man mo woman i brekem wan pat blong Deklereisen ia mo agensem eni fasin blong mekem se i gat diskrimineisen olsem.

Atikol 8

Evriwan i gat raet blong kasem wan stret fasin blong stretem problem we ol stret nasonol traebuno blong ol akt we oli go agensem ol stamba raet we Konstitusen o loa givim, oli mekem.

Atikol 9

Bambae man o woman i no save arestem narafala man o woman long fasin we i folem tingting blong hem nomo, fasin blong givim panismen o fasin blong mekem man i stap hemwan olsem panismen.

Atikol 10

Evriwan i gat raet blong ful ikwaliti long wan indipenden mo fea pablik hearing we wan indipenden mo fea tribunal i putum, long taem blong disaedem ol raet mo ol obligeisen blong hem mo blong eni kriminol jasmen agensem hem.

Atikol 11

- Eniwan we i gat jasmen blong wan rong agensem hem hemi gat raet blong stap olsem wan inosen man o woman go kasem taem we kot i pruvum se hemi gilti from se hemi mekem rong agensem loa long wan pablik traeol we hemi bin gat evri janis we hemi nidim blong difendem hemwan.

- Bambae man o woman i no gilti from wan rong we hemi mekem o wan aksen we hemi no mekem we i no wan rong folem nasonal mo intenasonal loa, long taem we man o woman ia i mekem aksen ia. Bambae i nogat wan panismen we i hevi bitim hemia we i aplae long taem ia we man o woman ia i bin mekem rong ia.

Atikol 12

Bambae man o woman i no save intefea wetem praevet laef, famili, hom or korespondens blong narafala man o woman folem tingting blong hem, mo no save spolem hae respek mo gudfala nem blong hem. Evriwan i gat raet blong loa i protektem hem agensem ol fasin blong intefea olsem o atak.

Atikol 13

- Evriwan i gat raet blong kasem fridom blong go long weaples hemi wantem go mo blong stap insaed long eria blong wanwan steit.

- Evriwan i gat raet blong livim eni kaontri, we i minim se kaontri blong hem tu mo blong hemi go bak long kaontri blong hem.

Atikol 14

- Evriwan i gat raet blong lukaotem mo stap long wan ples long wan narafala kaontri sipos hemi stap ronwe long ol fasin blong talem mo tritum nogud man o woman.

- Man o woman i no save yusum raet ia taem i gat prosekusen we i kamaot folem ol kraem we oli no kamaot from politik o from ol aksen we oli no folem ol eim mo prinsipol blong Unaeted Neisesn.

Atikol 15

- Evriwan i gat raet blong gat wan nasonaliti.

- Bambae wan man o woman i nogat raet blong kiaman long wan man o woman long nasonaliti blong hem o kiaman long raet blong jenisim nasonaliti blong hem.

Atikol 16

- Evri man mo woman long evri eij, nomata wanem reis, nasonaliti o rilijen, oli gat raet blong maret mo blong statem wan famili. Oli gat raet long ikwel raet long saed blong maret, long taem blong maret mo long taem we oli disolvem maret.

- Maret bambae i tekemples nomo taem we hemi tingting blong man mo woman ia blong tufala i maret.

- Famili hemi natural mo impoten grup unit blong sosaeti mo hemi gat raet blong sosaeti mo steit i protektem hem.

Atikol 17

- Evriwan i gat raet blong onem wan propeti hemwan mo tu wetem ol narafala man o woman tugeta.

- Folem tingting blong hem, bambae wan man o woman i no save kiaman long narafala man o woman from propeti blong hem.

Atikol 18

Evriwan i gat raet long fridom blong tingting, fridom blong morol tingting blong jasmen mo rilijen; raet ia hemi kavremap fridom blong jenisim rilijen o bilif blong hem, mo fridom blong hem hemwan o tugeta wetem ol narafala man o woman long komuniti mo long pablik o praevet laef, blong soem rilijen blong hem tru long fasin we hemi tijim, praktisim, wosip mo folem ol tijing blong rilijen blong hem o biliv blong hem.

Atikol 19

Evriwan i gat raet long fridom blong talem tingting blong hem mo talem long wei we hemi wantem; raet ia hemi kavremap fridom blong save gat ol difren tingting wetaot man i intefea mo blong risivim mo givimaot infomeisen mo ol tingting tru long niuspepa, televisen o radio nomata long ol baondri blong ol kaontri.

Atikol 20

- Evriwan i gat raet long fridom blong mit wanples mo grup tugeta long fasin we i gat pis long hem.

- Wan man o woman i no save fosem narafala man o woman blong stap long wan asosiesen.

Atikol 21

- Evriwan i gat raet blong tekpat long Gavman blong kaontri blong hem, daerek o tru long ol representativ we olgeta pipol oli jusum folem tingting blong olgeta.

- Evriwan i gat raet long semak janis blong kasem sevis blong Gavman long kaontri blong hem.

- Bambae pipol oli jusum kaen Gavman we oli wantem blong rul; fasin blong jusum Gavman ia bambae i kamaot tru ol eleksen long wanwan period mo bambae evri man mo woman i gat raet blong vot long sekret folem ol fasin blong fri vot.

Atikol 22

Evriwan, olsem memba blong sosaeti, i gat raet blong kasem sosol sekuriti mo hemi gat raet blong kasem ol ekonomik, sosol mo kaljarol raet blong hem we hemi nidim from respek blong hem mo blong mekem se hemi fri blong developem hemwan, hemia tru long help mo hadwok blong nasonol mo intenasonol komuniti mo folem oganaeseisen mo risos blong wanwan Kaontri.

Atikol 23

- Evriwan i gat raet blong wok, blong jusum wanem wok hemi wantem mekem, blong stap long ol gudfala kondisen blong wok mo blong gat proteksen agensem fasim blong nogat wok.

- Evriwan, wetaot diskrimineisen, i gat raet blong kasem ikwol pei blong mekem semak wok.

- Evriwan we i wok oli gat raet long stret mo gudfala pei we i mekem se hem mo famili blong hem i save gat wan gudfala laef we i soem se i gat respek, mo i kasem tu ol narafala kaen proteksen long sosol laef blong hem, sipos i gat nid.

- Evriwan i gat raet blong fomem mo joenem ol tred union blong protektem ol intres blong olgeta.

Atikol 24

Evriwan i gat raet blong spel mo enjoem hem, we i minim se i mas gat limit long ol haoa blong wok mo blong oli gat holidei wetem pei wanwan taem.

Atikol 25

- Evriwan i gat raet long wan standed blong laef we i stret long helt mo welfea blong hem mo famili blong hem, hemia long saed blong kakae, klos, haos mo medikol kea mo ol narafala sosol sevis, mo raet long sekuriti long taem we man o woman i no wok, i sik, wan pat blong bodi i nogat o no save wok gud, woman i lusum man blong hem o man i lususm woman blong hem, taem hemi olfala o taem hemi no save gat wan gudfala laef from sam samting we hemwan i no save kontrolem.

- Mama mo pikinini oli gat raet blong kasem spesel kea mo help. Evri pikinini, nomata we oli bon long mama mo papa we tufala i mared o no mared, bambae oli kasem semak protektek long sosol laef blong olgeta tu.

Atikol 26

- Evriwan i gat raet blong kasem edukeisen. Bambae edukeisen hemi fri, sipos i no long ol narafala level be bambae hemi hapen long ol elementeri mo fes level blong skul. Bambae evri pikinini i mas go long wan elementeri skul. Bambae i mas gat teknikol mo profesonal edukeisen we pipol i save folem sipos oli wantem mo bambae evri man mo woman i gat raet blong kasem hae edukeisen folem merit.

- Edukeisen bambae hemi blong developem fulwan ol defren kaen fasin blong man mo woman mo blong leftemap respek blong ol raet blong man mo woman mo ol stamba fridom. Edukeisen bambae hemi promotem fasin blong andastanem, luksave nid mo mekem fren wetem evri kaontri, evri difren kaen reis mo rilijes grup blong pipol mo bambae hemi mekem ol wok blong Unaeted Neisen blong kipim pis oltaem.

- Papa mo mama blong pikinini oli gat raet blong jusum kaen edukeisen we bambae pikinini blong tufala i kasem.

Atikol 27

- Evriwan i gat raet blong tekempat olsem hemi wantem long kaljarol laef blong komuniti, blong enjoem ol art mo serem ol save blong saens we i stap kam andap mo ol benefit blong hem.

- Evriwan i gat raet blong protektem ol morol mo materiol interes we i kamoat folem eni wok we man mo woman i prodiusum long saed blong saens, litereja mo art we hemi bin raetem.

Atikol 28

Evriwan i gat raet long wan sosol mo intenasonol oda we i mekem se oli save yusum fulwan ol raet mo fridom we oli stap insaed long Deklereisen ia.

Atikol 29

- Evriwan i gat diuti blong mekem i go long komuniti we tru long hem nomo bambae hemi fri blong save developem fulwan fasin blong hem olsem wan man o woman.

- Taem we man mo woman i stap yusum ol raet mo fridom ia, bambae evriwan i mas folem ol limit we oli stap insaed long loa blong mekem se man i luksave mo respektem ol raet mo fridom blong ol narafala pipol mo blong folem ol rul blong gudfala fasin, pablik oda mo jenerol welfea long wan demokratik sosaeti.

- Man mo woman i no save yusum ol raet mo fridom ia long wei we i agensem ol tingting mo prinsipol blong Unaeted Neisens.

Atikol 30

Wan man o woman i no save yusum wan pat blong Deklereisen ia blong mekem se Steit, o wan grup o man o woman i ting se hemi gat raet blong mekem eni aktiviti o blong mekem eni aksen we i go agensem ol raet mo fridom we i stap insaed long Deklereisen ia.

Mokrani Revolt

| Mokrani Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of French conquest of Algeria | |||||||

Tribes under the Mokrani revolt. Source : Djilali Sari, L'insurrection de 1871, SNED, Alger, 1972, p.29. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Algerian rebels: Algerian peasants |

France: Native auxiliaries | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 100,000 Kabyle cavalry, and 100,000 other fighters[1] | Army of Africa (86,000 men) plus native auxiliaries | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ≈ 2000 dead[2] | 2,686 dead[3] | ||||||

The Mokrani Revolt (Arabic: مقاومة الشيخ المقراني, lit. 'Resistance of Cheikh El-Mokrani'; Berber languages: Unfaq urrumi, lit. 'French insurrection') was the most important local uprising against France in Algeria since the conquest in 1830.

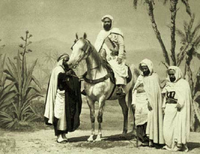

The revolt broke out on March 16, 1871, with the uprising of more than 250 tribes, around a third of the population of the country. It was led by the Kabyles of the Biban mountains commanded by Cheikh Mokrani and his brother Bou-Mezrag el-Mokrani, as well as Cheikh al-Haddad, head of the Rahmaniyya Sufi order.

Background

Cheikh Mokrani presentation

Cheikh Mokrani (full name el-Hadj-Mohamed el-Mokrani) and his brother Boumezrag (full name Ahmed Bou-Mezrag) came from a noble family - the Ait Abbas dynasty (a branch of the Hafsids of Béjaïa), the Amokrane, rulers, since the sixteenth century of the Kalâa of Ait Abbas in the Bibans and of the Medjana region.[4] In the 1830s, their father el-Hadj-Ahmed el-Mokrani (d. 1853), had chosen to form an alliance with the French : he allowed the Iron Gates expedition in 1839, becoming thus khalifa of the Medjana under the supervision of French authorities.[5] This alliance quickly proved to be a subordination - a decree of 1845 abolished the khalifalik of Medjana so that when Mohamed succeeded his father, his title was no more than “Bachagha” (Turkish: başağa = chief commander), and was part of the administration of the Bureaux arabes.[6]: 35 During the hardships of 1867, he gave his personal guarantee, at the request of the authorities, for important loans.

The context

The background of the revolt is as important as the revolt itself. In 1830, French army took up Algiers. Since then, France colonized the country, setting up its own administration all over Algeria. Shortly after 1830, a resistance rose up, led by Abd al-Kader, which lasted till 1847. French administrations and the France government decided to repress this movement which impacted both people and agriculture. The late 1860s were hard for the people of Algeria: between 1866 and 1868 they lived through drought, exceptionally cold winters, an epidemic of cholera and an earthquake. More than 10% of the Kabyle population died during this period.[1] Thus, at the end of the 1860s, Algeria was exhausted and the demography at its worst. To sum up all those events, on March 9, 1870, the French government decided to put a civilian regime in Algeria, which gave more advantages to French colonizers. In 1870, the creditors demanded to be repaid and the French authorities reneged on the loan on the pretext of the Franco-Prussian War, leaving Mohamed forced to pawn his own possessions. On June 12, 1869, Marshall MacMahon, the Governor General, advised the French government that “the Kabyles will stay peaceful as long as they see no possibility of driving us out of their country.”[7]

Under the French Second Republic, the country was governed by a Governor General and a large proportion was "military territory".[8][9] There were tensions between the French colonists and the army; the former favouring the abolition of the military territory as being too protective of the native Algerians.[10] Eventually, on March 9, 1870, the Corps législatif passed a law which would end the military regime in Algeria.[11] When Napoleon III fell and the Third French Republic was proclaimed, the Algerian question fell under the remit of the new Justice Minister, Adolphe Crémieux, and not, as previously, under the Minister of War. At the same time, Algeria was experiencing a period of anarchy. The settlers, hostile to Napoleon III and strongly Republican, took advantage of the fall of the Second Empire to push forward their anti-military agenda. Real authority devolved to town councils and local defence committees, and their pressure resulted in the Crémieux Decree.

Meanwhile, on September 1, 1870, the French army was defeated by the Prussian army in Sedan, and lost the French part of Alsace-Lorraine. The fact that France was at this time defeated by another country brought hope to Algerians. Indeed, the news of the French defeat on its border was spread thanks to the paper news. Then, Algerian protests began in public places, and in the South of Algeria, people committee were established to organized the revolt.

Revolt's origins

Algerians inhabitants and the Second Empire

A number of causes have been suggested for the Mokrani revolt. There was a general dissatisfaction among Kabyle notables because of the steady erosion of their authority by the colonial authorities. At the same time, ordinary people were concerned about the imposition of civilian rule on March 9, 1870, which they interpreted as imposing domination by the settlers, with encroachments on their land and loss of autonomy.[12]

The Cremieux decree

The Cremieux Decree of October 24, 1870, which gave French nationality to Algerian Jews was possibly another cause of the unrest.[6]: 119 [13] However some historians view this as doubtful, pointing out that this story only started to spread after the revolt was over.[14] This explanation of the revolt was particularly widespread among French antisemites.[15] News of the insurrectionary Paris commune also played a part.[16] Indeed, from March 18 until May 28, 1871, Paris was under the Commune, which was an autonomous commune administered under direct democracy principles. This Commune was also the hope to found a social and democratic Republic. Thus, the episode of the Paris Commune resonated in Algeria as a new possibility to take over the French administration established in Algeria.

Several months before the start of the insurrections, Kabyle village communities multiply gatherings of electing village assemblies ("tiǧmaʿīn", Arabic "ǧamāʿa") despite the colonial authorities having banned them from doing so. It must be emphasised that those "ǧamāʿa" were managing bodies to the population, therefore an obstacle to French policy . On social matters those assemblies would decide rules for the community. They were composed with a president "amin", a treasurer named a "ukil" and some men of the village elected to verify the members (patrilineage) or because they are really elder.

The first signs of actual revolt appeared in the mutiny of a squadron of the 3rd Regiment of Spahis in January 1871. The spahis (Muslim cavalry troopers in the French Army of Africa) refused to be sent to fight in metropolitan France,[17] claiming that they were only required to serve in Algeria. This mutiny began in Moudjebeur, near Ksar Boukhari on January 20, 1871, spread to Aïn Guettar (in the region of modern Khemissa, near Souk Ahras) on January 23, 1871, and soon reached El Tarf and Bouhadjar.[18]

Cheikh Mokrani's dissidence

The mutiny at Aïn Guettar involved the mass desertion of several hundred men and the killing of several officers. It took on a particular significance for the Rezgui family, whose members maintained that France, recently defeated by the Prussians, was a spent force and that now was the time for a general uprising. The Hanenchas responded to this call, killing fourteen colonists in their territory; Souk Ahras was besieged from 26th to 28 January, before being relieved by a French column, who then put down the insurgency and condemned five men to death.[18]

Mokrani submitted his resignation as bachagha in March 1871, but the army replied that only the civil government could now accept it. In reply, Mokrani wrote to General Augeraud, subdivisional commander at Sétif:[19]

"You know the matter which puts me at odds with you; I can only repeat to you what you already know - I do not wish to be the agent of the civil government..... I am preparing myself to fight you; today let each of us take up his rifle."[13]

The revolt spreads

The spahi mutiny was reignited after March 16, 1871, when Mokrani took charge of it.[13] On March 16, Mokrani led six thousands men in an assault on Bordj Bou Arreridj.[20] On April 8, French troops regained control of the Medjana plain. The same day, Si Aziz, son of Cheikh al-Haddad, head of the Rahmaniyya order, proclaimed a holy war in the market of Seddouk.[13] Soon 150,000 Kabyles rose,[21] as the revolt spread along the coast first, then into the mountains to the east of the Mitidja and as far as Constantine. It then spread to the Belezma mountains and linked with local insurrections all the way down to the Sahara desert.[22] As they spread towards Algiers itself, the insurgents took Lakhdaria (Palestro), 60 km east of the capital, on the 14th of April. By April, 250 tribes had risen, or nearly a third of Algeria's population. One hundred thousand “mujahidin”, poorly armed and disorganised, were launching random raids and attacks.[12]

French counterattack

The military authorities brought in reinforcements for the Army of Africa; Admiral de Gueydon, who took over as Governor General on March 29, replacing Special Commissioner Alexis Lambert, mobilised 22,000 soldiers.[1] Advancing from Palestro towards Algiers, the rebels were stopped at Boudouaou (Alma) on April 22, 1871, by colonel Alexandre Fourchault under the command of General Orphis Léon Lallemand; on May 5,[1] Mohamed el-Mokrani died fighting at Oued Soufflat, halfway between Lakhdaria (Palestro) and Bouira in an encounter with the troops of General Félix Gustave Saussier.[20]

On 25 April, the Governor General declared a state of siege.[23] Twenty columns of French troops marched on Dellys and Draâ El Mizan. Cheikh al-Haddad and his sons were captured on July 13, after the battle of Icheriden.[24] The revolt only faded after the capture of Bou-Mezrag, Cheikh Mokrani's brother, on January 20, 1872.[25]

Repression

During the fighting, around 100 European civilians died, along with an unknown number of Algerian civilians.[1] After fighting ceased, more than 200 Kabyles were interned[26] and others deported to Cayenne[26] and New Caledonia, where they were known as Algerians of the Pacific.[27] Bou-Mezrag Mokrani was condemned to death by a court in Constantine on March 27, 1873.

The Kabylie region was subjected to a collective fine of 36 millions francs, and 450,000 hectares of land were confiscated and given to new settlers, many of whom were refugees from Alsace-Lorraine,[26][1] especially in the region of Constantine. The repression and confiscations forced a lot of Kabyles to leave the country.[1]

Chronology of battles

| N° | Battle | Current location | From | To | Leaders | Zawiyas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Battle of Bordj Bou Arréridj | Bordj Bou Arréridj | March 16, 1871 | June 2, 1871 | ||

| 02 | Battle of Palestro | Lakhdaria | April 14, 1871 | May 25, 1871 | ||

| 03 | Battle of Laazib Zamoum | Naciria | April 17, 1871 | May 22, 1871 | ||

| 04 | Battle of Bordj Menaïel | Bordj Menaïel | April 18, 1871 | May 18, 1871 | ||

| 05 | Battle of the Issers | Issers | April 18, 1871 | May 13, 1871 | ||

| 06 | Battle of the Col des Beni Aïcha | Thenia | April 19, 1871 | May 8, 1871 | ||

| 07 | Battle of Alma | Boudouaou | April 19, 1871 | April 23, 1871 |

Judicial trial of rebel leaders

After the end of the hostilities of the insurrection of Cheikh Mokrani, the Algerian rebel leaders who were captured alive appeared before the Assize Court of Algiers on December 27, 1872, on a count of indictment and an act of accusation linked to the sacking of the French colonies, the assassinations, fires and looting which sparked heated debates on this extremely important affair.[28]

Several criminal charges weighed on each of the offender who all, without exception, had taken part in the insurrection. The prosecution of the court made charges which weighed on each of the accused for the crimes alleged against these main leaders and leaders of the 1871 insurrection.

The list of these incarcerated rebel leaders is as follows:

- Cheikh Boumerdassi (1818-1874) alias "Mohamed ben Hamou ben Abdelkrim".

- Abdelkader Boumerdassi (born 1837) alias "Abdelkader ben Hamou ben Abdelkrim".

- Omar ben Zamoum[29]

- Mohamed Saïd Oulid ou Kassi (Oukaci)

- Hadj Ahmed ben Dahman

- Si Saïd ben Ali

- Si Saïd ben Ramdan

- Mohamed ben M'Ra (Merah)

- Hadj Mohamed ben Moussa

- Mohamed Amzian Oulid Yahia

- Mohamed ben Bouzid

- Moussa ben Ahmed ben Mohamed

- Saïd ben Ahmed ben Mohamed

- Ali ben Haoussin

- Amar bel Abbas

- Ahmed ben Zoubir

- Ahmed Khoia ben Mohamed

- Mohamed ben Aissa

- Mohamed ben Belkassem

- Ahmed ben Sliman

- Mohamed bel Aid

- Mohamed ben Yahia

- Ali N'Amara ou el Hadj Saïd

- Si Saïd ben Mohamed

- Omar ben Haminided

- Ahmed Oulid el hadj Ali

- Belgassem ben Gassem

- Mohamed ben Lounés

- Ali ben Amran

- Ahmed ben Amar

- Hassein el Achebeb

- Smaîn ben Omar

- Si Mohamed ou El Hadj ou Alali

- Mohamed bou Bahia

A long list was then enumerated of the names of other subordinate rebel Algerian leaders and natives who participated in the Alma and Palestro massacres.

After reading the indictment, including the whole so-called Palestro affair, which lasted about an hour and a half, the president of the assize court urged the jurors to follow on the notebook that was given to them, and where the name of each offender was written at the top of a page, the individual examination which will be carried out and to take notes due to the length of the debates.

Deportation to New Caledonia

The leaders of the Mokrani Revolt after their capture and trial in 1873 were either executed, subjected to forced labor, or deported and exiled to the Pacific and New Caledonia.[30][31]

A convoy of 40 Kabyle insurrectional leaders was undertaken on the ship La Loire on June 5, 1874, towards the L'Île-des-Pins for deportation. They were the symbols of Algerian resistance against the French occupation.[32]

The specialist in history Malika Ouennoughi drew up a list of these 40 deportees, whose names follow:[33]

- Cheikh Boumerdassi, born in 1818 at Ouled Boumerdès, was a marabout, with the matricule: 1301.

- Ahmed ben Ali Seghir ben Mohamed Ouallal, born in 1854 at Baghlia, was a farmer, with the matricule: 852.

- Ahmed Kerbouchene, born in 1829 at Larbaâ Nath Irathen, was a farmer, with the matricule: 883.

- Ahmed ben Mohamed ben Barah, born in 1829 at Dar El Beïda, was a farmer, with the matricule: 859.

- Ahmed ben Belkacem ben Abdallah, born in 1822 at Oued Djer, was an indigene, with the matricule: 1306.

- Ahmed ben Ahmed Bokrari, born in 1838 at Bou Saâda, was an farmer, with the matricule: 857.

- Abdallah ben Ali ben Djebel, born in 1844 at Guelma, was a spahi, with the matricule: 803.

- Ahmed ben Salah ben Amar ben Belkacem, born in 1809 at Souk Ahras, was an caïd, with the matricule: 854.

On May 18, 1874, the leaders of the Mokrani Revolt were embarked at the Port of Brest in the 9th convoy of deportees from the ship La Loire placed under the orders of captain Adolphe Lucien Mottez (1822-1892).[34]

They numbered 50 Algerian deportees, and were reinforced with 280 other French convicts from the jails of Fort Quélern, and at their head the marabout Cheikh Boumerdassi.[35]

This ship arrived on June 7, at the anchorage of the port of Île-d'Aix, where it embarked 700 passengers, including 40 women, and 320 other French deportees.[36]

On June 9, he left for Nouméa, and it was therefore the 9th convoy of deportees that left France to then stop on June 23, in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, to arrive in Nouméa on October 16, 1874.

After a last stopover in Santa Catarina Island, La Loire arrives in Nouméa on October 16, 1874, after a journey of 133 days.[37]

There will be around 5 deaths at sea and on November 10, of the same year, the ship "La Loire" left Nouméa to return to France after having disembarked the convicts from Kabylie.[38]

On the 40 or 50 Algerians mentioned, 39 were destined for simple deportation to the L'Île-des-Pins, and only one of them for deportation to a fortified enclosure.

On the 300 convoys in the convoy, 250 suffered from scurvy, and will die in the weeks following their arrival in New Caledonia according to Roger Pérennès.[39][40]

In Mémoires d'un Communard, Jean Allemane evokes a deadly epidemic of dysentery which decimated the transported people that La Loire had just landed, and who were buried in large numbers.[41][42]

Begun at dawn, the burial of the corpses was a task which often did not end until nightfall, and the men who had died of dysentery presented a morbid spectacle.[43][44]

More than two hundred convicts who had come by the Loire died almost immediately after their disembarkation.[45]

However Louis-José Barbançon reports that on the civil status registers of the Bagne of L'Île-des-Pins, which were very well kept, only 28 deaths of convicts who came by "La Loire" appeared in the 6 months after arrival of the ship.[46][47]

See also

- List of participants in Mokrani Revolt

- Zawiyas in Algeria

- Rahmaniyya

- Zawiyet Sidi Boumerdassi

- Cheikh Boumerdassi

- Fort Quélern

- French ship Prince Jérôme

Bibliography

- Bozarslan, Hamit. Sociologie politique du Moyen-Orient, Collection Repères, La Découverte, 2011.

- Brett, Michael. “Algeria 1871–1954 - Histoire de l’Algérie Contemporaine. Vol. 11: De L’insurrection de 1871 Au Déclenchement de La Guerre de Libération (1954). By Charles-Robert Ageron. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1979. Pp. 643. No Price Stated.” Journal of African history 22.3 (1981): 421–423. Web.

- Brett, Michael. “Algeria 1871–1954.” The Journal of African History 1981: 421–423.

- De Grammont, H.-D. “RINN, Histoire de l’insurrection de 1871 en Algérie.” Revue Critique d’Histoire et de Littérature 25.2 (1891): 301–. Print.

- De Peyerimhoff, Henri. “La colonisation officielle en Algérie de 1871 à 1895.” Revue Économique Française 1928: 369–. Print.

- De Peyerimhoff, Henri de, and Comité Bugeaud. La colonisation officielle de 1871 à 1895 : [rapport à M. Jonnart, gouverneur général de l’Algérie]. Paris Tunis: Société d’éditions géographiques, maritimes et coloniales Comité Bugeaud, 1928. Print.

- Jalla, Bertrand. “L’autorité judiciaire dans la répression de de 1871 en Algérie.” Outre-mers (Saint-Denis) 88.332 (2001): 389–405. Web.

- Merle, Isabelle . “Algérien en Nouvelle-Calédonie : Le destin calédonien du déporté Ahmed Ben Mezrag Ben Mokrani.” L’année du Maghreb 20 (2019): 263–281. Web.

- Mottez, Adolphe Lucien (1875). Deux Expériences faites à bord de la Loire pendant un voyage en Nouvelle-Calédonie. 1874-1875. p. 83.

- Lewis, Bernard. Histoire du Moyen-Orient, Albin Michel, 2000.

- Robin, Joseph, Mahé, Alain. L’insurrection de la Grande Kabylie en 1871. Saint-Denis: Éditions Bouchène, 2018. Print.

- Sicard, Christian. La Kabylie en feu : Algérie 1871. Paris: Georges Sud, 2013. Print.

References

- Barbançon, Louis-José (January 1995). La terre du lézard. ISBN 9782307118138.

No comments:

Post a Comment