Friday, 17 May 2024

La pendaison de crémaillère, de notre enfant et de nos petits-enfants au dessus des flammes!

Ma Chère et tendre n'a cessé de pendre notre enfant et nos petits enfants AU DESSUS DES FLAMMES pendant 40 ans !

La pendaison de crémaillère, une fête moderne et traditionnelle.

27 juillet 2016, mis à jour le 24 août 2016

https://www.nextories.com/blog/2016/07/pendaison-cremaillere-une-fete-traditionnelle/

Après avoir effectué un déménagement il est d’usage de réunir ses proches dans son nouveau logement pour fêter son emménagement, c’est ce qu’on appelle la pendaison de crémaillère. D’où nous vient cette coutume ? Pourquoi s’est-elle perpétuée jusqu’à nos jours ? En regardant les autres pays on s’aperçoit que chacun a une tradition différente pour fêter l’emménagement dans un nouveau logement, c’est pourquoi, vous seriez bien inspiré vous aussi d’offrir cette jolie fête à vos proches. Voici nos conseils d’expert en déménagement pour que votre emménagement soit synonyme de fête.

Une fête traditionnelle pour marquer l’emménagement.

D’une manière générale, toutes les cultures ont leurs propres façons de fêter la construction d’une nouvelle habitation. En France c’est la « pendaison de crémaillère » qui marque l’emménagement dans un nouveau logement.

L’origine de la pendaison de crémaillère.

L’expression « pendaison de crémaillère » est d’origine médiévale.

À cette époque quand une habitation était terminée on avait coutume

d’inviter à manger toutes les personnes ayant participé à la

construction de la maison. Or au Moyen-Âge les marmites étaient

suspendues au-dessus de l’âtre grâce à une tige en métal

servant à régler la hauteur de la marmite par rapport aux flammes et

donc la température de la cuisson. Or cette tige en métal s’appelait la « crémaillère ».

Sans crémaillère, on ne pouvait suspendre de marmites et faire cuire un

repas, c’est pourquoi la crémaillère était la dernière chose installée

dans la nouvelle habitation. La pendaison de crémaillère était

l’occasion d’inviter toutes les personnes qui avaient aidé à la

construction de la maison à partager le premier repas du foyer.

L’expression « pendaison de crémaillère » est d’origine médiévale.

À cette époque quand une habitation était terminée on avait coutume

d’inviter à manger toutes les personnes ayant participé à la

construction de la maison. Or au Moyen-Âge les marmites étaient

suspendues au-dessus de l’âtre grâce à une tige en métal

servant à régler la hauteur de la marmite par rapport aux flammes et

donc la température de la cuisson. Or cette tige en métal s’appelait la « crémaillère ».

Sans crémaillère, on ne pouvait suspendre de marmites et faire cuire un

repas, c’est pourquoi la crémaillère était la dernière chose installée

dans la nouvelle habitation. La pendaison de crémaillère était

l’occasion d’inviter toutes les personnes qui avaient aidé à la

construction de la maison à partager le premier repas du foyer.

Les fêtes d’emménagement dans les coutumes étrangères

Chez nos chers voisins la fête d’emménagement ne s’appelle pas la pendaison de crémaillère mais peut prendre des formes diverses qui montrent la richesse des différentes cultures européennes.

En Angleterre la tradition s’appelle le « Housewarming » ce qui veut dire le « chauffage de la maison », cela consistait à inviter famille et amis une fois la maison terminée pour en chasser les mauvais esprits ou esprits errants. Chaque invité devait ramener une bûche et le premier feu allumé lors de la « Housewarming » permettait de purifier la maison et la rendre habitable.

En Allemagne si vous êtes invités à une crémaillère la coutume consiste à amener différents présents aux habitants du nouveau logement. Parmi les présents traditionnellement offerts on retrouve souvent du sel et du pain, synonymes de prospérité pendant le Moyen-Âge. De même en Italie il est bien vu d’amener du vin ou de l’huile d’olive lors de l’équivalent italien de la pendaison de crémaillère afin d’amener l’esprit de la fête dans le nouveau logement.

L’organisation d’une crémaillère.

Si vous avez déménagé il n’y a pas longtemps c’est–à–vous de perpétuer cette tradition joyeuse et vivante en organisant votre propre pendaison de crémaillère. Voici nos conseils si vous organisez ou si vous vous rendez à une pendaison de crémaillère.

Quand, comment, avec qui fêter sa crémaillère ?

Une pendaison de crémaillère s’organise généralement dans les 3 mois suivants le déménagement afin de montrer votre nouveau logement quand vous le découvrez encore.

Il existe deux écoles concernant la pendaison de crémaillère : ceux qui organisent leurs crémaillères quelques jours après leur déménagement, au milieu des cartons pas encore déballés et de la peinture fraiche, et ceux qui attendent d’être bien installés avant de montrer leur nouveau nid douillet. Les deux options ont leurs avantages et leurs inconvénients : faire la fête au milieu des cartons permet une ambiance plus informelle mais attendre d’avoir mis sa touche personnelle dans son nouveau logement permet de montrer son « vrai » chez-soi.

En général une pendaison de crémaillère est une fête regroupant la famille et les amis proches mais vous pouvez élargir ce cercle en fonction de la taille de votre logement. N’hésitez pas à inviter vos voisins cela peut être l’occasion de faire connaissance et commencer à nouer des liens. Les voisins sont souvent oubliés mais ce sont eux qui sont le plus directement concernés par votre emménagement, ne l’oubliez pas !

Quel cadeau offrir pour une crémaillère ?

Question difficile mais qui demande une réponse. En effet, passé le quart de siècle, vous risquez d’être invité à de plus en plus de crémaillères… N’ayez crainte, voici nos conseils pour vous sortir par le haut de cette terrible épreuve. Les cadeaux offerts pour une pendaison de crémaillère sont généralement peu onéreux, un budget entre 20 et 30 euros est tout à fait correct, vous n’êtes pas invité à un mariage non plus. Privilégiez des objets pratiques pour aider la ou les personnes qui emménagent : des appareils électroménagers comme un fouet électrique ou une petite chaine hi-fi conviennent parfaitement pour des cadeaux communs. Un peu de décoration peut aussi être apprécié (tableaux, bibelots) pour aider à décorer un peu ces nouveaux logements toujours un peu vide au début mais attention à bien connaître les goûts de vos hôtes en matière de décoration sous risque de voir votre cadeau gentiment mis au fond d’un placard. Enfin offrir des cadeaux symboliques tel que le sel (prospérité), le pain (fertilité), les sucreries (la bonne humeur) ou le vin (l’esprit de fête) peut être une manière de signifier votre bonne intention à l’égard des nouveaux occupants.

La pendaison de crémaillère a pu prendre différentes formes à travers l’Europe mais cette tradition venue du Moyen-Age s’est remarquablement maintenue en France, désormais c’est une fête moderne qui donne de la joie chaque années à toutes les personnes qui changent de logements. Nous ne pouvons donc que vous encourager à organiser votre crémaillère et cela vous donnera d’autant plus de plaisir que vous avez mis de temps à trouver votre nouveau logement et organiser votre déménagement.

Wednesday, 1 May 2024

MUSLIMS IN THE AMERICAS BEFORE AMERIGO VESPUCCI AND CHRISTOPHER COLOMBUS

Muslims in America: A forgotten history

For more than 300 years, Muslims have influenced the story of the US – from the ‘founding fathers’ to blues music today.

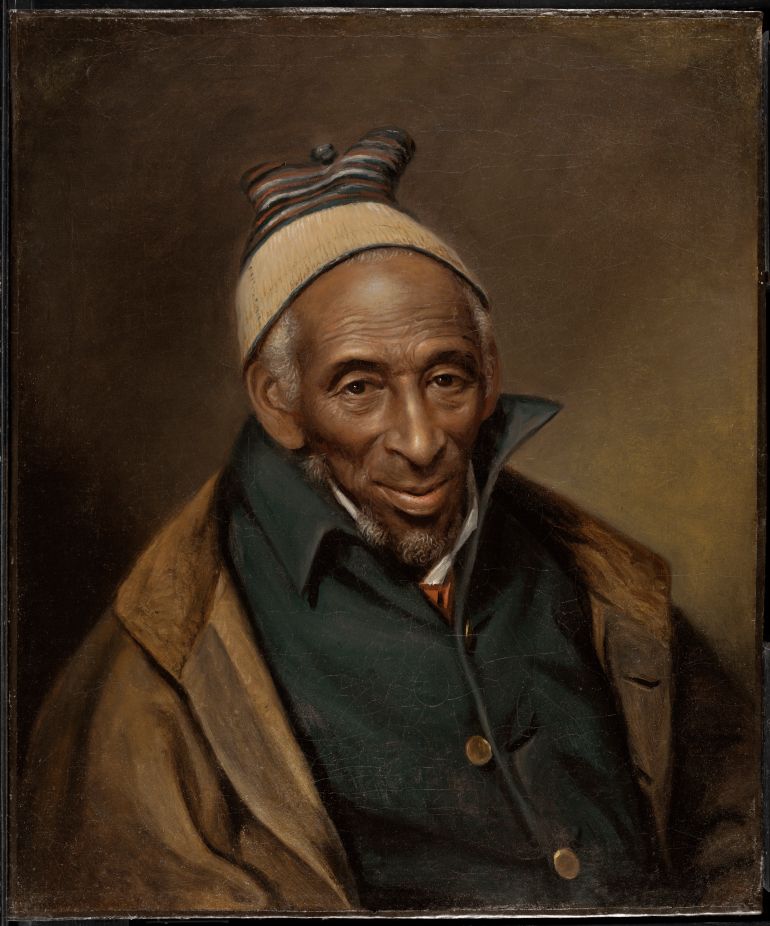

Omar ibn Said, a Muslim, was born in 1770 in Senegal and by the time of his death, he had been enslaved for 56 years. In 2021, Omar, an opera about his life, will premiere at the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsKnow your history: Understanding racism in the US

Analysis: Toppling racist statues makes space for radical change

Muslims are usually thought of as 20th-century immigrants to the US, yet for well over three centuries, African Muslims like Omar were a familiar presence. They had grown up in Senegal, Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Benin and Nigeria where Islam was known since the 8th century and spread in the early 1000s.

Estimates vary, but they were at least 900,000 out of the 12.5 million Africans taken to the Americas. Among the 400,000 Africans who spent their lives enslaved in the United States, tens of thousands were Muslims.

Though they were a minority among the enslaved population, Muslims were acknowledged like no other community. Slaveholders, travellers, journalists, scholars, diplomats, writers, priests and missionaries wrote about them. Founder of Georgia James Oglethorpe, Presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State Henry Clay, author of the US national anthem Francis Scott Key, and portraitist of the Founding Fathers Charles W Peale were acquainted with some of them.

Visible manifestations of faith

Part of the Muslims’ conspicuousness was due to their continued observance, whenever possible, of the most noticeable tenets of their religion. Prayer, the second pillar of Islam, was one of these visible manifestations of faith noted by enslaved and enslavers alike.

In his 1837 autobiography, Charles Ball, who escaped slavery, related in great detail the story of a man who prayed aloud five times a day in a language others did not understand. He added, “I knew several, who must have been, from what I have since learned, Mohamedans; though at that time, I had never learned of the religion of Mohamed.”

Charles Spalding Willy had this to say about Bilali from Guinea, enslaved by his grandfather on Sapelo Island, Georgia: “Three times each day he faced the East and called upon Allah.” He witnessed other “devout Mussulmans, who prayed to Allah morning, noon and evening.”

Yarrow Mamout, another highly visible Muslim, was taken from Guinea in 1752 when he was about 16. After 44 years of slavery, he was freed and bought a house in Washington, DC. Mamout was a kind of celebrity who was “often seen and heard in the streets singing Praises to God – and conversing with him,” stated noted artist Charles Willson Peale.

In the 1930s, men and women formerly enslaved in Georgia described how their relatives and others prayed several times a day: they knelt on mats, bowed, said strange words, and had “strings of beads” or misbahs. As Bilali pulled the beads, one descendant recalled, he said “Belambi, Hakabara, Mahamadu.”

Sign up for Al Jazeera

Americas Coverage Newsletter

It is hard to imagine how people in dismal poverty could give alms, the third pillar of Islam, but still, charity proved to be the most widespread and resilient of all the Muslims’ religious practices.

In the Sea Islands, the women left their mark on this tradition. In the 1930s, their descendants recalled with fondness the rice cakes their mothers gave to children. There was a word for it: Saraka, followed after the sharing by “Ameen, Ameen, Ameen.”

Rice cakes are the charity still offered by West African Muslim women on Fridays. The cake is not called saraka, but the act of giving is a sadaqa, a freewill offering, and that word is uttered as the women give it.

Reflecting the Muslims’ influence, non-Muslims all over the Caribbean to this day offer saraka, unaware of its Islamic origin.

Fasting and dietary requirements

There is no doubt that Islam’s fourth pillar, fasting, was exceedingly hard for people underfed and overworked. Nevertheless, Bilali and his large family used to fast during Ramadan. And so did his friend Salih Bilali. Abducted in Mali when he was about 14, 60 years later he was still “a strict Mahometan; [he] abstains from spirituous liquors, and keeps the various fasts, particularly that of the Rhamadan” wrote his “owner”, James Hamilton Couper.

Omar ibn Said was said to have fasted too. Others whose lives were not recorded may have used the same subterfuge as Muhammad Kaba in Jamaica: Whenever he had to fast, he pretended to be sick.

Several testimonies mention Islam’s dietary restrictions. Throughout his long life, Yarrow Mamout told people, “it is no good to eat Hog [and] drink whiskey is very bad.”

In Mississippi, the son of a prince acknowledged the difficulty of adhering to these rules since slaveholders provided the food. He said “in terms of bitter regret, that his situation as a slave in America, prevents him from obeying the dictates of his religion. He is under the necessity of eating pork but denies ever tasting any kind of spirits.”

In South Carolina, a man only known as Nero was more fortunate, he drew his ration in beef instead. By fasting and refusing certain food Muslims were not only remaining faithful to their religion, they were also asserting a degree of control over their lives.

Distinguished by their dress

In addition to respecting the tenets of Islam, Muslims distinguished themselves, when possible, by the way they dressed. In Georgia, some women wore veils while men sported Turkish fez or white turbans.

An 1859 article described how, each morning, Omar ibn Said nailed the end of a long strip of white cotton to a tree and, holding the other end, wrapped it around his head, fashioning a turban. Daguerreotypes show him with printed fabric around his head or a wool hat. In his portrait, painted in 1819 by Charles W Peale, Mamout wore the same kind of hat as Omar’s.

In 1733, the Senegalese Ayuba Suleyman Diallo insisted on being immortalised in his “country dress” with a white turban and a robe. Likewise, some Muslims in Trinidad, Brazil, and Cuba were described as wearing “flowing robes”, skullcaps and wide pants.

By short-circuiting the coarse, demeaning slave clothes, the Muslims who could do so were reclaiming a bit of ownership of their own bodies, while stating their fidelity to their religion.

Curiosity and literacy

Besides being visible, Muslims generated much curiosity because of their literacy, an Islamic requirement because believers need to read the Quran.

This literacy was acquired in schools and, for the most educated, in local or foreign institutions of higher learning. This particularity set them apart from the non-Muslim Africans as well as many illiterate Americans, enslaved and free.

A slaveholder looking for a 30-year-old recent arrival listed only one characteristic in an 1805 runaway notice: he was a man “of grave countenance who writes the Arabic language”.

Two years later, Ira P Nash, a physician and land surveyor, brought to Thomas Jefferson’s attention – in three letters and one meeting – the tribulations of two Muslims. Captured in Kentucky, they escaped to Tennessee where they were jailed and escaped twice more. He gave Jefferson two pages they had written in Arabic. They included the last surah (chapter) of the Quran, al-Nas, Humanity, which speaks of refuge with Allah and evil, a perfect analogy to their situation.

Looking for a translation Jefferson sent the papers to scholar and abolitionist Robert Patterson. He thought the writings were about the men’s “history, as stated by themselves”.

Presumably, based on what that story would reveal, the president was willing to “procure the release of the men if proper”. However, their trace was lost before he could intervene.

Writing for fellow Muslims

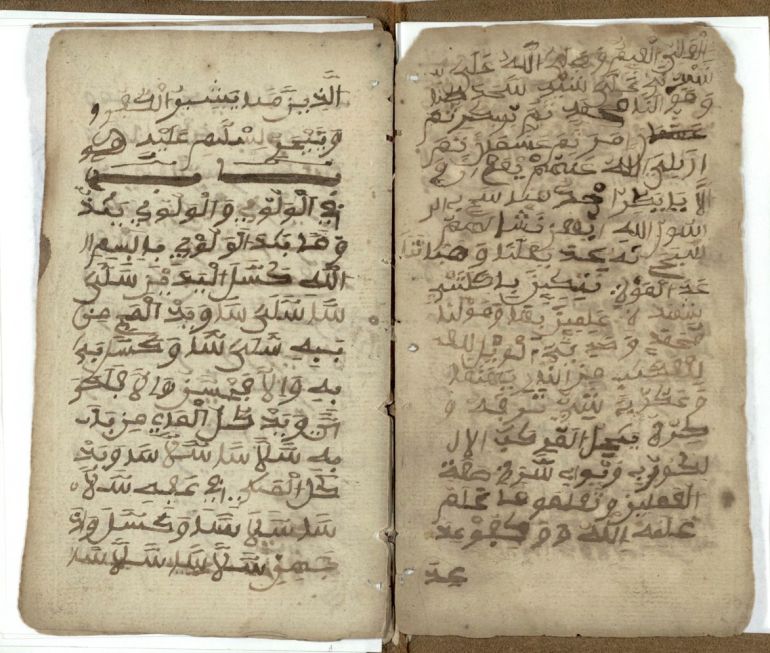

Today, manuscripts, from Brazil and Panama to the Bahamas, Trinidad and Haiti still exist. Written by anonymous Muslims and a few known ones, they cover Quranic chapters, prayers, talismans, invocations, and admonitions for the Muslims to remain faithful to Islam. Several are linked to the 1835 Muslim uprising in Bahia.

In about 1823 Muhammad Kaba Saghanughu, who had been captured in 1777 on his way to Timbuktu and deported to Jamaica, wrote a 50-page document in Arabic. Addressed to the “community of Muslim men and women,” it is an instructional manual on praying, marriage and ablutions, and contains commentaries and references to classic Islamic texts.

In contrast to autobiographies by formerly enslaved people, including Africans such as Olaudah Equiano, the Muslims were writing for their own community, not a Western audience.

In the US, Bilali wrote a 13-page document, part of a work by the 10th-century Tunisian Ibn Abu Zayd al-Qairawani. It was written on paper produced in Italy for the North African market, which raises intriguing questions as to how he acquired it.

Salih Bilali, wrote his owner, “reads Arabic, and has a Koran (which however, I have not seen) in that language, but does not write it.” Similarly, Bilali who “kept all the plantation ‘Acts’ in Arabic … was buried with his Koran and praying sheep skin.”

These casual mentions of Qurans on remote plantations beg the question of where they got them. Perhaps, as other memorisers of the Quran did in the Americas, they wrote them themselves.

The Muslims who became famous were only a handful but many others, as accomplished, remained nameless.

William Brown Hodgson, a former diplomat posted in North Africa and a slaveholder, stated in 1857: “There have been several educated Mohammedan slaves imported into the United States.”

In 1845, he informed the French Société d’ethnologie that “a Foulah prince, named Omar, is presently a slave in the United States and will be able to procure precious elements for a detailed notice on his nation.”

Hodgson had tried to get information – probably for the same purpose – from Muslims but had to stop due to slaveholders’ hostility.

Similarly, Theodore Dwight, the secretary of the American Ethnological Society, observed in 1871 that several Africans in different parts of the country were literate and he had “obtained some information from some of them”.

Unfortunately, he too encountered “insuperable difficulties in the way in slave countries, arising from the jealousy of masters, and other causes.”

Writing for freedom

Ayuba Suleyman Diallo made the most of his literacy. A trader and Quranic teacher from the Islamic State of Bundu in Senegal, he was abducted in 1730 in Gambia and sold to captain Stephen Pike of the Arabella.

Diallo told him his father would pay for his freedom and he was allowed to dispatch an acquaintance to his hometown. But the Arabella left before Diallo could be freed.

From Maryland, he wrote a letter to his father and gave it to a slave dealer with instructions to remit it to Pike. The letter did not reach him but ended up in London in the hands of James Oglethorpe, the deputy governor of the Royal African Company and future founder of Georgia. After reading the translation, Oglethorpe arranged for Diallo’s release and transportation to England.

The Senegalese arrived in London in April 1733. He met the royal family and helped renowned physician and naturalist Sir Hans Sloane – whose private collection was the foundation of the British Museum, the British Library and the Natural History Museum – translate Arabic documents. Before returning to Bundu in July 1734, he posed for painter William Hoare and wrote three copies of the Quran from memory. One was sold in 2013 for 21,250 British pounds ($28,040) to the Dar El-Nimer Collection for Art & Culture in Beirut.

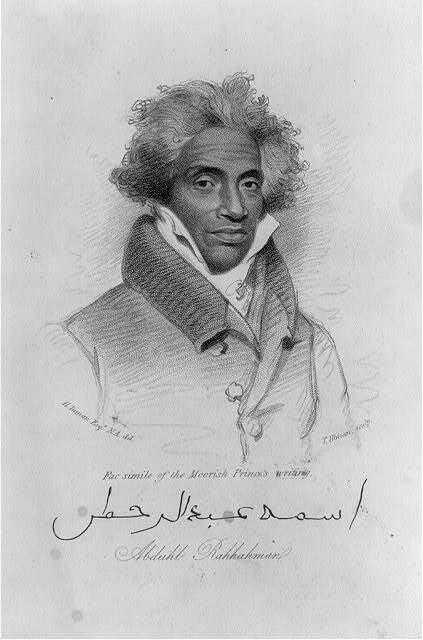

In Mississippi, Ibrahima abd al-Rahman followed in Diallo’s path with a letter he wrote in 1826. Thirty-eight years earlier the then 26-year-old son of the Muslim ruler of Futa Jallon in Guinea had been captured during a war. His letter was sent to Thomas Mullowny, the American consul in Morocco. He took it to Sultan Abd al-Rahman II, who asked for Ibrahima’s release. Secretary of State Henry Clay presented the case to President John Quincy Adams who devoted a passage to the matter in his diary on July 10, 1827.

After 39 years in Mississippi, Ibrahima was freed and left for Liberia in 1829 along with his American-born wife. He died shortly thereafter. Eight children and grandchildren were freed with the $3,500 he had raised for that purpose among abolitionists before leaving the US. They settled in Liberia, but seven relatives remained enslaved.

Challenging stereotypes

If his literacy didn’t free Omar ibn Said, it largely improved his situation. After he ran away in 1810 from an “evil man … an infidel who did not fear Allah”, Omar was captured as he prayed in a church and thrown in jail as a runaway. With pieces of coal, he covered the walls with pleas, in Arabic, to be released. The brother of a North Carolina governor bought him, gave him light tasks and furnished him with paper and Christian proselytisation.

Omar’s 1831 autobiography, written in Arabic, subtly denounced his enslavement with the help of Surat al-Mulk, which states that God has the power over all; in effect refuting his “owner’s” supremacy.

Professors Mbaye Bashir Lo at Duke and Carl Ernst at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have closely analysed his 17 known manuscripts. They found that he quoted from memory from a variety of works, including one by a 12th-century Andalusian Sufi master and a 16th-century Egyptian theological poem.

Much was made of Omar’s alleged conversion to Christianity and Francis Scott Key helped procure him a Bible in Arabic. Omar also had a Quran, which was said to be his most precious possession. Tellingly, his last known manuscript, in 1857, was Surat al-Nasr (the Victory) as in the victory of Islam against the “unbelievers” and other enemies. This was the last surah revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.

To be sure, the stereotype of Africans as uncivilised idolaters used as justification for their enslavement did not align with literate, monotheist people. Therefore, Muslims were often misrepresented as Arabs, Moors, and “descendants of the Arabian Mahomedans who migrated to Western Africa”.

The American Colonization Society, whose objective was to deport free Black people to Liberia, envisioned freed Muslims, like Ibrahima, as a conduit to the “civilising” of the continent and, strangely enough, its Christianisation.

The blues

The imprint of enslaved African Muslims can still be seen today. Arabic terminology survives in the Gullah language of South Carolina, in Trinidadian and Peruvian songs, in the Caribbean saraka, and in a variety of religions such as Candomble, Umbanda and Macumba in Brazil, Vodun in Haiti, and Regla Lucumi and Palo Mayombe in Cuba.

Moreover, a significant Muslim contribution, the blues, has been acknowledged by major musicologists since the 1970s. The roots of the blues can be found in the field holler – a solo, non-instrumental, slow tune with elongated words, pauses, and melisma, all constitutive elements of the Islamic style of singing and reciting.

What musicologists did not recognise, however, is that the holler was a direct product not of the Muslims’ memories, but of Islamic practices that endured in the US such as prayers, the recitation of the Quran, Sufi chants, and the adhan, the call to prayer.

In particular, the closeness to the adhan of WD “Bama” Stewart’s “Levee Camp Holler”, recorded in 1947 at Parchman prison in Mississippi, is quite extraordinary. When both are juxtaposed, it is hard to tell when one ends and the other starts.

The blues is one of the most lasting and overlooked contributions of African Muslims to American culture.

Another might be the ring shout of the American South, Jamaica, and Trinidad. A religious rite during which people turn in a circle, it was thought to be an African dance with a perplexing name since there is no shouting. Another explanation was proposed in the 1940s. One tour around the Ka’ba is called a shawt, which sounds close to the word “shout” in English. Like the pilgrims do in Mecca, the American shouters turn counterclockwise around a sacred structure, such as the church, the altar, or a dedicated second altar. Could Muslims have “reinvented” the major episode of the Hajj?

A forgotten history

Over time, the story and even the presence of African Muslims in the Americas faded from memory. But since the tragedy of 9/11, there has been a growing interest in this forgotten history, a stunning discovery to most.

African American Muslims used it to claim an ancient lineage and immigrant communities to show that Islam, far from being foreign, was as American as Christianity.

Today, people in the wider Islamic world are increasingly interested in this international history of Islam.

As Africans and as Muslims, the people who lived their faith in the dreadful oppression of American slavery contributed to the social, religious and cultural fabric of this country. The Muslims’ legacy, acknowledged or not, lives on. Their story is an African story, a Muslim story, and an American story.

Muslims of early America

Muslims came to America more than a century before Protestants, and in great numbers. How was their history forgotten?

is a historian and a senior editor at Aeon. He was a junior fellow at the Harvard Society of Fellows and a faculty member at the American University of Beirut and the American University in Cairo. His book The Origins of American Religious Nationalism came out in paperback in 2016 and has been widely reviewed.

Edited byBrigid Hains

4,300 words

The first words to pass between Europeans and Americans (one-sided and confusing as they must have been) were in the sacred language of Islam. Christopher Columbus had hoped to sail to Asia and had prepared to communicate at its great courts in one of the major languages of Eurasian commerce. So when Columbus’s interpreter, a Spanish Jew, spoke to the Taíno of Hispaniola, he did so in Arabic. Not just the language of Islam, but the religion itself likely arrived in America in 1492, more than 20 years before Martin Luther nailed his theses to the door, igniting the Protestant reformation.

Moors – African and Arab Muslims – had conquered much of the Iberian peninsula in 711, establishing a Muslim culture that lasted nearly eight centuries. By early 1492, the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella completed the Reconquista, defeating the last of the Muslim kingdoms, Granada. By the end of the century, the Inquisition, which had begun a century earlier, had coerced between 300,000 and 800,000 Muslims (and probably at least 70,000 Jews) to convert to Christianity. Spanish Catholics often suspected these Moriscos or conversos of practising Islam (or Judaism) in secret, and the Inquisition pursued and persecuted them. Some, almost certainly, sailed in Columbus’s crew, carrying Islam in their hearts and minds.

Eight centuries of Muslim rule left a deep cultural legacy on Spain, one evident in clear and sometimes surprising ways during the Spanish conquest of the Americas. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, the chronicler of Hernán Cortés’s conquest of Meso-America, admired the costumes of native women dancers by writing ‘muy bien vestidas a su manera y que parecían moriscas’, or ‘very well-dressed in their own way, and seemed like Moorish women’. The Spanish routinely used ‘mezquita’ (Spanish for mosque) to refer to Native American religious sites. Travelling through Anahuac (today’s Texas and Mexico), Cortés reported that he saw more than 400 mosques.

Islam served as a kind of blueprint or algorithm for the Spanish in the New World. As they encountered people and things new to them, they turned to Islam to try to understand what they were seeing, what was happening. Even the name ‘California’ might have some Arabic lineage. The Spanish gave the name, in 1535, taking it from The Deeds of Esplandian (1510), a romance novel popular with the conquistadores. The novel features a rich island – California – ruled by black Amazonians and their queen Calafia. The Deeds of Esplandian had been published in Seville, a city that had for centuries been part of the Umayyad caliphate (caliph, Calafia, California).

Across the Western hemisphere, whenever they arrived at new lands or encountered native peoples, Spanish conquistadores read the requerimiento, a stylised legal pronouncement. In essence, it announced a new state of society: offering Native Americans the chance to convert to Christianity and submit to Spanish rule, or else bear responsibility for all the ‘deaths and losses’ that would follow. A formal and public announcement of the intent to conquer, including an offer to the faithless of a chance to submit and become believers, is the first formal requirement of jihad. Following centuries of war with the Muslims, the Spanish had adopted this practice, Christianised it, called it the requerimiento, and took it to America. Iberian Christians might have thought Islam wrong, or even diabolical, but they also knew it well. If they thought it strange, it must be counted a very familiar strange.

Join over 250,000+ newsletter subscribers

Our content is 100 per cent free and you can unsubscribe anytime.

By 1503, we know that Muslims themselves, from West Africa, were in the New World. In that year, Hispaniola’s royal governor wrote to Isabella requesting that she curtail their importation. They were, he wrote, ‘a source of scandal to the Indians’. They had, he wrote, repeatedly ‘fled their owners’. On Christmas morning 1522, in the New World’s first slave rebellion, 20 Hispaniola sugarmill slaves rose and began slaughtering Spaniards. The rebels, the governor noted, were mostly Wolof, a Senegambian people, many of whom have been Muslim since the 11th century. Muslims were more likely than other enslaved Africans to be literate: an ability rarely looked upon with favour by plantation-owners. In the five decades following the 1522 slave rebellion on Hispaniola, Spain issued five decrees prohibiting the importation of Muslim slaves.

Muslims thus arrived in America more than a century before the Virginia Company founded the Jamestown colony in 1607. Muslims came to America more than a century before the Puritans founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. Muslims were living in America not only before Protestants, but before Protestantism existed. After Catholicism, Islam was the second monotheistic religion in the Americas.

The popular misunderstanding, even among educated people, that Islam and Muslims are recent additions to America tells us important things about how American history has been written. In particular, it reveals how historians have justified and celebrated the emergence of the modern nation-state. One way to valorise the United States of America has been to minimise the heterogeneity and scale – the cosmopolitanism, diversity and mutual co-existence of peoples – in America during the first 300 years of European presence.

The past is those bits and pieces of history that a society selects in order to sanction itself

The writing of American history has also been dominated by Puritan institutions. It might no longer be quite true, as the historian (and Southerner) U B Phillips complained more than 100 years ago, that Boston had written the history of the US, and largely written it wrong. But when it comes to the history of religion in America, the consequences of the domination of the leading Puritan institutions in Boston (Harvard University) and New Haven (Yale University) remain formidable. This ‘Puritan effect’ on seeing and understanding religion in early America (and the origins of the US) brings real distortion: as though we were to turn the political history of 20th-century Europe over to the Trotskyites.

Think of history as the depth and breadth of human experience, as what actually happened. History makes the world, or a place and people, what it is, or what they are. In contrast, think of the past as those bits and pieces of history that a society selects in order to sanction itself, to affirm its forms of government, its institutions and dominant morals.

The forgetting of early America’s Muslims is, then, more than an arcane concern. The consequences bear directly on the matter of political belonging today. Nations are not mausoleums or reliquaries to conserve the dead or inanimate. They are organic in that, just as they are made, they must be consistently remade, or they atrophy and die. The virtual Anglo-Protestant monopoly over the history of religion in America has obscured the half-a-millenium presence of Muslims in America and has made it harder to see clear answers to important questions about who belongs, who is American, by what criteria, and who gets to decide.

What then should ‘America’ or ‘American’ mean? With its ‘vast, early America’ programme, the Omohundro Institute, the leading scholarly organisation of early American history, points to one possible answer. ‘Early America’ and ‘American’ are big and general terms, but not so much as to be nearly meaningless. Historically, they are best understood as the great collision, mixing and conquest of peoples and civilisations (and animals and microbes) of Europe and Africa with the peoples and societies of the Western hemisphere, from the Greater Caribbean to Canada, that began in 1492. From 1492 to at least about 1800, America, simply, is Greater America, or vast, early America.

Muslims were part of Greater America from the start, including those parts of it that would become the United States. In 1527, Mustafa Zemourri, an Arab Muslim from the Moroccan coast, arrived in Florida as a slave on a disastrous Spanish expedition led by Pánfilo de Nárvaez. Against all odds, Zemourri survived and made a life for himself, travelling from the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico through what is now the Southwestern US, as well as Meso-America. He struggled through servitude to native peoples before fashioning himself into a well-known and respected medicine man.

In 1542, Cabeza de Vaca, one of the four survivors of the Nárvaez expedition, published the first European book, later known as Adventures in the Unknown Interior of America, devoted to North America. De Vaca told of the disasters that befell the conquistadores, and of the eight years that the survivors spent wandering through North and Meso-America. De Vaca acknowledged that it was Zemourri who became the indispensable one: ‘It was,’ wrote de Vaca, ‘the negro who talked to them all the time.’ The ‘them’ were the Native Americans, and it was Zemourri’s facility with native languages that kept the men alive and even, after a time, allowed them a kind of flourishing.

Zemourri saw far more of the present-day US, its lands and peoples, than any of the country’s ‘founding fathers’ – even any several of them combined. Laila Lalami captures all of this and more in her excellent novel The Moor’s Account (2014), which follows Zemourri through his childhood in Morocco, slavery in Spain and, ultimately, to a mysterious end in the American Southwest. If there is such a thing as a best version of the American pioneer or frontier spirit, some resonating experience of adaptation and reinvention that can stamp itself on a nation and peoples, it is difficult to find one who represents it better than Zemourri.

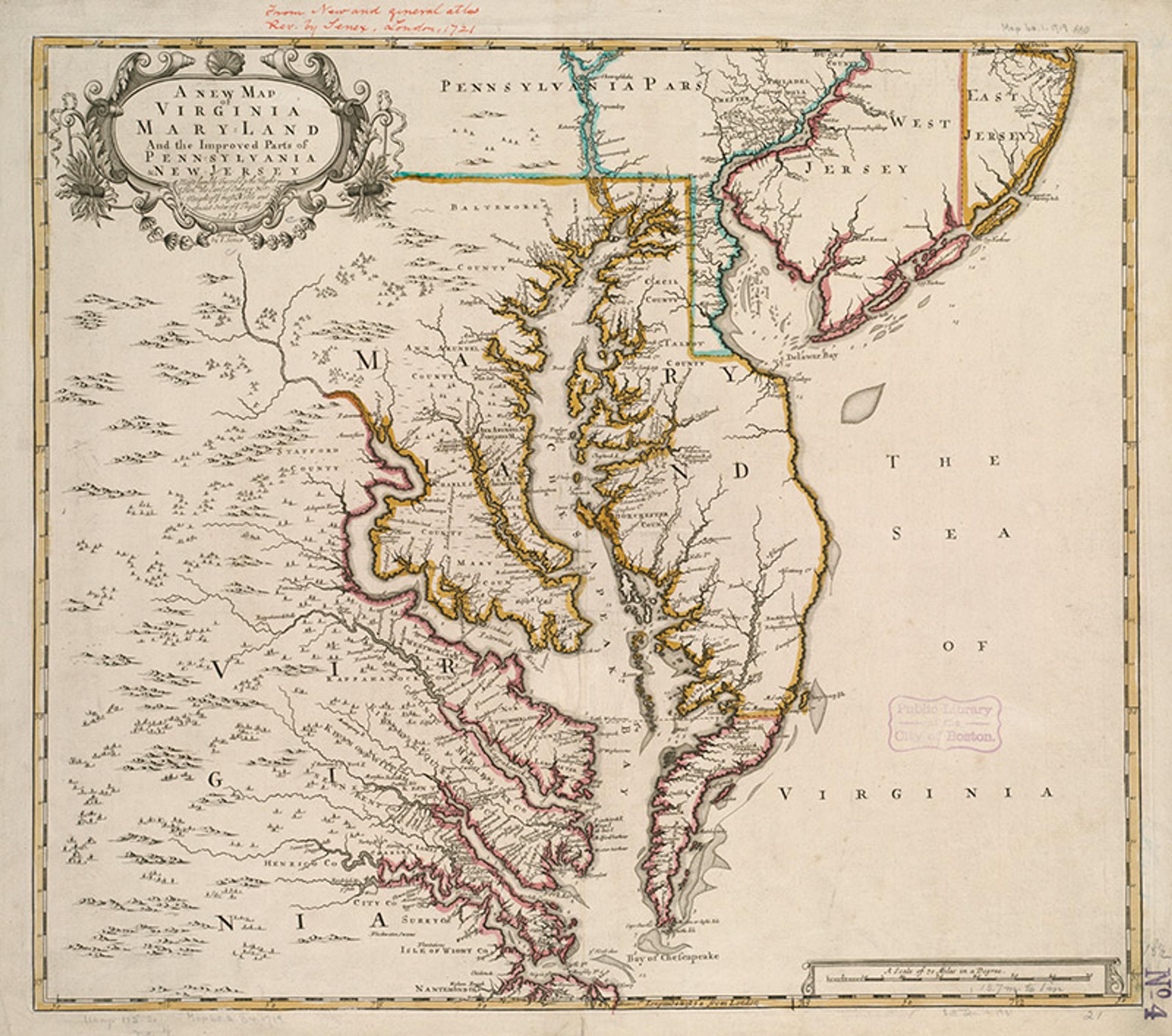

Between 1675 and 1700, the beginnings of plantation society in the Chesapeake allowed local slavemasters to bring more than 6,000 Africans to Virginia and Maryland. This boom in the trade propelled an important change in American life. In 1668, white servants in the Chesapeake had outnumbered black slaves by five to one. By 1700, that ratio had been reversed. Over the first four decades of the 18th century, more Africans came to the Chesapeake. Between 1700 and 1710, growing planter wealth led to the importation of another 8,000 enslaved Africans. By the 1730s, an additional 2,000 slaves per year, at least, came to the Chesapeake. The American Chesapeake was transforming from a society with slaves (most societies in human history have had slaves) to a slave society, which is far more unusual. In a slave society, slavery is the foundation of economic life and the master-slave relationship serves as the exemplary social relation, a model for all others.

The first generations of Africans brought to North America were likely to work in the fields alongside and sleep under the same roof as their owners. They also, notes historian Ira Berlin in Many Thousands Gone (1998), tended to be eager converts to Christianity. They hoped conversion would help them secure social standing. West Africans brought during the late-17th and first half of the 18th century to work as slaves in Virginia, Maryland and the Carolinas came from different parts of Africa, or from the West Indies, than had these earlier ‘charter’ generations. They were more likely to be Muslims, and much less likely to be of mixed descent. Christian missionaries and planters in the 18th century complained that this ‘plantation generation’ of slaves showed little interest in Christianity. Missionaries and planters criticised what they saw as the slaves’ practice of ‘pagan rites’. Islam could, to an extent, persist on these plantations of American slave society.

Similarly, between 1719 and 1731, the French took advantage of civil war in West Africa to enslave thousands, bringing almost 6,000 enslaved Africans directly to Louisiana. Most of them came from Futa Toro, a region around the Senegal River straddling present-day Mauritania and Senegal. Islam had reached Futa Toro in the 11th century. Ever since, Futa has been known for its scholars, jihad armies and theocracies, including the Imamate of Futa Toro, a theocratic state that lasted from 1776 to 1861. Late-18th- and early 19th-century African conflicts in the Gold Coast (what is now Ghana) and Hausaland (mostly present-day Nigeria) also reverberated in the Americas. In the former, the Asante defeated a coalition of African Muslims. In the latter, the jihadists ultimately prevailed but in the process lost many compatriots to the slave trade and the West.

The song of Solomon was also (and might have first been) the song of Suleyman

Ayuba Suleyman Diallo is the best-known Muslim of 18th-century North America. He was of the Fulbe, an Islamic people of West Africa. As early as the 16th century, European traders enslaved many Fulbe, sending them to be sold in America. Diallo was born in Bundu, an area between the Senegal and Gambia rivers, under an Islamic theocracy. He was captured by a British slave trader in 1731, and eventually sold to a Maryland slaveowner. An Anglican missionary recognised Diallo writing in Arabic and offered him wine to test if he was a Muslim. Later, a British lawyer who wrote an account of Diallo’s enslavement and transport to Maryland anglicised his first name Ayuba to Job and his surname Suleyman to Ben Solomon. In this way, Ayuba Suleyman became Job Ben Solomon.

,-Ayuba-Suleiman-Diallo-Courtesy--Dar-El-Nimer.jpg?width=3840&quality=75&format=auto)

In such a fashion, the experience of enslavement and passage to America saw many Arabic names Anglicised; Quranic names rendered into something familiar from the King James Bible. Musa became Moses, Ibrahim became Abraham, Ayuba became Jacob or Job, Dawda became David, Suleyman became Solomon and so on. Toni Morrison drew on the history of Islamic naming practices in America in her novel Song of Solomon (1977). The title of the novel comes from a folk song that holds clues to the history of its protagonist, Milkman Dead, and his family. The fourth verse of the song begins: ‘Solomon and Ryna, Belali, Shalut / Yaruba, Medina, Muhammet too.’ These names came from African Muslims enslaved in Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, the Carolinas and elsewhere in America. The song of Solomon, in other words, was also (and might have first been) the song of Suleyman.

Re-naming slaves (sometimes in derogatory or jesting ways) was an important tool of planter authority, and rarely neglected. Nonetheless, across North America, Arabic names remain part of the historical record. Louisiana court records of the 18th and 19th century show proceedings related to Almansor, Souman, Amadit, Fatima, Yacine, Moussa, Bakary, Mamary and others. Court records from 19th-century Georgia detail legal proceedings involving Selim, Bilali, Fatima, Ismael, Alik, Moussa and others. Newbell Puckett, a 20th-century sociologist, spent a lifetime collecting ethnographic material about Afro-American cultural life. In his Black Names in America: Origins and Usage, Puckett documented more than 150 common Arabic names among those of African descent in the South. Sometimes an individual had both – an Anglo or ‘slave name’ serving for official purposes, while the Arabic prevailed in practice.

It is difficult to know to what extent the persistence of Arabic names related to continued religious practice or identity, but it seems unlikely to be totally disconnected. A 1791 Georgia newspaper advertisement for a runaway slave, for example, read: ‘new Negro Fellow, called Jeffray … or IBRAHIM’. Given the careful control that slaveowners exerted over naming, there must have been many men called ‘Jeffray’ who were really Ibrahim, many women called ‘Masie’ who were actually Masooma, and so on.

Lorenzo Dow Turner, a mid-20th-century scholar of Gullah (a creole language spoken on the Sea Islands off America’s Southeastern coast) documented ‘about 150 names of Arabic origin’ relatively common on the Sea Islands alone. They include Akbar, Alli, Amina, Hamet and many others. On plantations in the early 19th-century Carolinas, Moustapha was a popular name. Arabic names do not necessarily make one a Muslim, at least not in the Maghreb or Levant, where Arabs are Christians and Jews too. But it was the spread of Islam that brought Arabic names to West Africa. So these African and Afro-American Aminas and Akbars, or at least their parents or grandparents, were almost surely Muslims.

Out of fear, Spanish authorities had tried to ban Muslim slaves from their early American settlements. In the more established and secure slave society of 18th- and 19th-century Anglo-America, some planters preferred them. In both cases, the reasoning was the same: Muslims stood apart, possessed authority, and exerted influence. One publication – Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves in the Sugar Colonies (1803), focused on the West Indies – advised that Muslims ‘are excellent for the care of cattle and horses, and for domestic service’ but ‘little qualified for the ruder labours of the field, to which they never ought to be applied’. The author noted that on the plantations: ‘Many of them converse in the Arabic language.’

An early 19th-century Georgia slaveowner who claimed to represent an enlightened approach to slavery advocated making ‘professors of the Mahommedan religion’ into ‘drivers, or influential negroes’ on plantations. He claimed that they would exhibit ‘integrity to their masters’. He and others cited instances of Muslim slaves siding with the Americans, against the British, in the War of 1812.

Some Muslim slaves in 19th-century America had themselves been slaveowners, teachers or military officers in Africa. Ibrahima abd al-Rahman was a colonel in the army of his father, Ibrahima Sori, an emir or governor in Futa Jallon, in what is now Guinea. In 1788, at age 26, al-Rahman was captured in war, purchased by British traders, and transported to America. Al-Rahman spent nearly 40 years picking cotton in Natchez, Mississippi. Thomas Foster, his owner, called him ‘Prince’.

In 1826, through an unlikely chain of events, al-Rahman came to the attention of the American Colonization Society (ACS). This society was organised for the goal of deporting people of African descent in the US ‘back’ to Africa. Comprised of many of the country’s leading philanthropists and some of its most powerful politicians, the ACS combined versions of both white nationalism and Christian universalism. For more than two years, the ACS pressured Foster, who finally agreed to free al-Rahman but refused to free his family. In an attempt to raise money to buy his family’s freedom, al-Rahman went to the free cities in the Northern US, where he busked at fundraising events and parades – wearing ‘Moorish’ costume and writing al-Fatiha, the opening of the Quran, on pieces of paper for donors (and leading them to believe it was the Lord’s Prayer).

Al-Rahman was a Muslim and he prayed as a Muslim. When he met with the leaders of the ACS, he told them he was a Muslim. Yet Thomas Gallaudet, a prominent Yale-educated evangelical and education activist, gave al-Rahman a Bible in Arabic and asked that they pray together. Holding out the prospect of transport to Africa and gainful employment, Arthur Tappan, America’s leading philanthropist, pressured al-Rahman to become a Christian missionary and to help extend the Tappan brothers’ lucrative commercial empire into Africa.

The African Repository and Colonial Journal, the ACS magazine, described how al-Rahman would ‘become the chief pioneer of civilisation to unenlightened Africa’. They saw him planting ‘the cross of the Redeemer upon the furthermost mountains of Kong!’ This, in capsule form, was the Puritan effect at work. First, al-Rahman’s religion and self-identification was denied. Second, powerful institutions specialising in writing, recordkeeping, publishing and education (essential technical skills in crafting history into the past) acted to misrepresent him.

Puritans were neither beloved by nor necessarily representative of New Englanders

The details of al-Rahman’s story might be unusual. But his experience as an American Muslim facing an Anglo-Protestant monopoly bent on manufacturing a ‘Christian’ country is not. Islam developed, in part, to exist above the great linguistic and cultural differences of Asia and Africa: al-Rahman spoke six languages. Anglo-American evangelical Protestantism is, by contrast, a younger, narrower religion. It took shape in the culturally circumscribed region of the North Atlantic and in a dynamic relationship with both capitalism and nationalism. It aims not at transcending heterogeneity but rather (as Gallaudet and Tappan were attempting with al-Rahman) to homogenise.

How many people shared al-Rahman’s basic experience? How many Muslims were there in America between, say, 1500 and 1900? How many in North America? Sylviane A Diouf is the great historian of the subject. In what is probably a conservative figuring, she writes in Servants of Allah (1998), ‘there were hundreds of thousands of Muslims in the Americas’ and ‘that may be all we can say about numbers and estimates.’ Of the 10 million or more enslaved Africans sent to the New World, more than 80 per cent went to the Caribbean or Brazil. Nonetheless, many more Muslims came to early America than did Britons arriving during the height of Puritan colonisation. The high point of Puritan settlement during the ‘Great Migration’, between 1620 and 1640, saw just 21,000 Britons come to North America. Perhaps 25 per cent of these came as servants whose Puritan sentiments cannot be presumed. By 1760, New England was home to – at most – 70,000 Congregationalists (the church of New England Puritans).

Despite these relatively small numbers, the Puritans succeeded in becoming the schoolmasters to a nation. Yet in some respects, New England is also the loser in the rise of the US. It reached its peak of economic and political influence in the 18th century. Despite its prominent role in US independence, it has never been the centre of economic or political power either in the British colonies in North America, nor in Greater America, nor even in the US.

Seen simply as one of many New World colonies, New England was in notable respects an outlier. It was demographically unique (for its settlement by families), religiously sectarian, politically anomalous and, from the perspective of Europe, economically secondary. Even the phrase ‘Puritan New England’ can be misleading. Fish, timber and maritime commerce – specifically, their trade with the West Indian plantations – not religion, made life in 17th- and 18th-century New England what it was. Puritans were neither beloved by nor necessarily representative of New Englanders. In the early 17th-century Massachusetts Bay Colony, for example, a listener once heckled a Puritan minister, interrupting his sermon with: ‘New England’s business is cod not God!’

Some of the same qualities that made the Puritans so unusual helped them excel at writing history. They were exceptionally adept in literacy, education, textual exegesis and institution-building. These skills enabled them, distinctly among Americans, to rise to the challenge of addressing what the sociologist Roger Friedland has called ‘the problem of collective representation’ in the modern world. Before modern nations, histories of peoples had been genealogies. A people were those who descended from an ancestor: Abraham or Aeneas, for example, and thus naturally related. The ideal of the modern nation presented a new problem. A nation is supposed to be one common people, who share fundamental, even inherent qualities – but not an ancestry, nor a king or queen.

At the end of the 18th century, almost no one quite knew how to represent a common people. In North America, the Puritans came the closest. They thought and wrote of themselves not as a common people but a chosen people, a people not sharing descent from a lord but following the Lord. For rendering the history of a heterogeneous population into a national unity, it was by no means a perfect fit. But it would have to do.

The Puritan effect has excluded much, including the long and enduring presence of Muslims and Islam in America, as well as some of the integrity and poignancy of the Puritan experience on its own terms, distinct from its contributions to US national history. The domination of the Puritan institutions has given colonial New England an outsized role. Over two centuries, mores have changed a great deal, but great 19th-century historians such as Francis Parkman and Henry Adams share with their 20th- and 21st-century successors Perry Miller, Bernard Bailyn and Jill Lepore a commitment to finding America, and the national origins of the US, in 18th-century New England.

One of the most perverse feats of Puritan history-writing has been to claim the mantle of religious freedom as some Anglo-Protestant commitment. In fact, Puritans and evangelical Protestants in America have always conjured and persecuted religious enemies: Native Americans, Catholics, Jews, communists, LGBT people, Muslims and, sometimes especially, other Protestants. Neither John Winthrop, Cotton Mather nor any part of the Puritan squirearchy suffered real religious persecution. Possessing power, as Anglo-Protestants in America have, is not entirely compatible with the basis for some of the claims to moral authority of Christianity. Nor is it wholly consonant with the idea of America as a land of religious freedom, an asylum for the persecuted, as Tom Paine put it in 1776.

If there is any religious group who represents the best version of religious freedom in America, it is Muslims such as Zemourri and al-Rahman. They came to America under conditions of genuine oppression, and struggled for the recognition of their religion and the freedom to practise it. In contrast to Anglo-Protestants, Muslims in America have demurred the impulse to tyrannise others, including Native Americans.

The most persistent consequence of the Puritan effect has been a continuing commitment to producing a past focused on how the actions, usually courageous and principled, of Anglo-Protestants (almost always in New England and the Chesapeake) led to the United States of America, its government and its institutions. The truth is that the history of America is not primarily an Anglo-Protestant story, any more than the history of the West more broadly. It might not be a straightforward or self-evident matter what, exactly, constitutes ‘the West’. But the more global era in history inaugurated by the European colonisation of the Western hemisphere must be a significant part of it.

If the West means, in part, the Western hemisphere or North America, Muslims have been part of its societies from the very beginning. Conflicts over what the American nation is and who belongs to it are perennial. Answers remain open to a range of possibilities and are vitally important. Historically, Muslims are Americans, as originally American as Anglo-Protestants. In many ways, America’s early Muslims are exemplars of the best practices and ideals of American religion. Any statement or suggestion to the contrary, no matter how well-meaning, derives from either intended or inherited chauvinism.